Hapkido has its roots in Japan

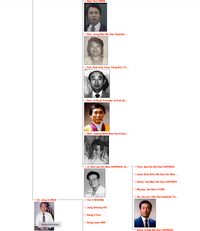

Descendants Report for Sogaku TAGEDA

Sogaku TAGEDA (1859 - 1943) and his student Morihei UESHIBA (1883)

Hapkido was born in Korea

The development of Hapkido began in Korea during the 1910s, when the Japanese ruled the country.

Choi Yong-sul (1904-1986) was brought to the Japanese city of Moji at the age of about eight, according to his own recollections.

In the following decades, he learned Japanese Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu under the samurai Takeda Sōkaku (1859-1943).

In spite of the lack of evidence that Choi directly trained under Takeda, it is unquestionable that he studied Jiu-Jitsu.

This context makes it necessary to mention that Takeda also taught Ueshiba Morihei (1883-1969).

Thus, Hapkido and Aikido share the same roots.

Besides Choi, other Koreans had learned Daitō-ryū Aiki-jūjutsu in Japan, including Dr. Chang In Mok (born 1912).

Similarly to Choi, after the Japanese colonial period ended in 1945, he returned to the Korean city of Daegu and taught martial arts there.

In contrast to Choi, he produced few students and was primarily an oriental medicine practitioner.

A few of the notable students were: Jang Seeung Ho, Song Joon Hwi, Choi, Han Young, Hu Il Wong (teacher of Peter and Joseph Kim), and Song Il Hun.

The Chun Ki Do style was developed by Han-Young Choi, a top student of Dr. In-Mok.

Roman Nikolaus Urban was one of Han Young Choi's top students, spreading Chun Ki Do Hapkido throughout Europe and Africa.

Choi Yong-sul initially referred to the martial art he had learned as Yawara, the old Japanese term for Jujitsu.

Due to his long stay in Japan, he spoke about 70% Japanese and only about 30% Korean after his return to Korea.

While he changed nothing or very little in the techniques, he changed the name of his martial art several times.

So he called them Yu Sul (“soft technique”, this is the direct translation of jujitsu into Korean), Yu Kwon Sul (“soft fist technique”) and Hapki Yu Kwon Sul (“soft fist technique in unity with Ki”).

I. Dr. Jang In MOK (1912) Chun Ki Do is a small line of martial arts

II. Choi, Han Young 10th Dan Chun Ki Do, World

III. Daniel Ray Walker, 9th black belt Chun Ki Do, USA

V. Justin Castillo, 5th degree black belt Chun Ki Do Las Cruces, USA

V. Marcy Shoberg 6th black belt, Albuquerque New, México

III. Sam Choi 8th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, Korea, USA

III. Roman Nikolaus 8th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, Africa, Europe

V. Akoto Raphael Silvanus 7th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, Ghana, Africa

V. Jörg Moßmann 7th degree black belt, Germany, Europe

V. Franz-Josef Ludwig 6th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, Germany

III. Jaeshin Cho 7th degree black belt Chun Ki Do

III. Daniel Rogers, 9th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, USA (1958-2001)

V. Antony Rogers 5 Dan Chun Ki Do, Louisiana, USA

III. Gregory Jump, 7th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, USA, Germany

V. Jens Schimmel 4. Dan Silent Stream Hapkido, Germany, Europe

III. Antoine Hines 6th degree black belt Chun Ki Do, Las Vegas, USA

I. Choi, Yong-Sul (1904) All other Hapkido styles are descended from this lineage

- II. Ji, Han-Jae Sin Moo HAPKIDO 10.Dan, Hur Il WOONG,

- II.-Sub CHOI

- II. Il Chang 10th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. S. Kim 9th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. Ke Te 7th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. , Bong-Soo 9th Dan Hapkido International Hapkido Fed

- II. Soo Lim 9th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. Hwan Park 9th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. Moo Woong

- II. Moo KWAN

- II. , Jung-Soo 9th Dan, student #8 of Choi, Yong-Sul. HapKiDo school in Korea (Taegu City)

- II. , Jung-Yoon Han PUL

- II. , Joo-Bang Founder of Hwarang DO

- II. Wollmershauser 8th Dan Hapkido American Hapkido ASSOCIATION

- II. , Kwang-Sik 10th Dan Hapkido World Hapkido

- II. , Nam Sun PARK, Rim, Jong-Bae 9th Dan Hapkido Rim's Hapkido ASSOCIATION

- II. , In-Hyuk Founder of Kuk Sool WON

- II. , Kwang-Wha Moo Sool Kwan HAPKIDO

- II. Seeung HO, Song Il HUN

- II. , Sea-Oh 6th Dan HAPKIDO

- II. Shik Shin 9th Dan Sin Moo Hapkido, vice-president Sin Moo Hapkido ASSOCIATION

- II. , Tae-Man 9th Dan HAPKIDO, Myung

- II. Nam Dae Han Hapkido Hyub HWE

- II. , Se-Lim 10th Dan Hapkido The Korea Hapkido FEDERATION

- II. , Il-Hak 8th Dan HAPKIDO

One of my friends Grandmaster Detlef Klos, he wrote 2 books and published in his last book his Hapkido Friends and called them so nice Wonderful people / Friends in Germany

Ein guter Freund, Großmeister Detlef Klos, schrieb 2 Bücher und in seinem letzten Buch nannte er seine Hapkido Freunde, mit der netten Geste, als Wunderbare Menschen / Freunde in Deutschland

Über den Autor und weitere Mitwirkende

Detlef Klos interessierte sich schon als Jugendlicher für Asien, asiatische Geschichte und asiatische Kultur. So kam er bereits 1966 zum Judosport und begann ein Jahr später mit der koreanischen Kampfkunst Hapkido. Diese betreibt er nunmehr seit über 50 Jahren und wurde wegen seiner Fähigkeiten und seines Einsatzes im Hapkido vom koreanischen Weltverband mit dem 9. Dan und dem Titel Großmeister geehrt

Hapkido, die koreanische Kampfkunst, ist weltweit bekannt für ihre einzigartigen waffenlosen Selbstverteidigungstechniken. Für die fortgeschrittenen Kampfkünstler enthält diese Kunst jedoch darüber hinaus zahlreiche Techniken, bei denen auch Hilfsmittel eingesetzt werden können, um einen potenziellen Gegner zu besiegen. Diese Hilfsmittel, in diesem Buch als „Waffen“ bezeichnet, können traditionelle asiatische Waffen wie auch heutige gebräuchliche Alltagsgegenstände sein. In diesem Buch im DIN A4 Format werden beispielhafte Techniken dieser Gruppe mit Text und über 2500 Farbfotos beschrieben und dem fortgeschrittenen Kampfkünstler eine Vielzahl von Trainingsmöglichkeiten geboten. Alle Techniken werden Schritt für Schritt erlernbar dargestellt.

Hapkido, the Korean martial art, is known worldwide for its unique weaponless self-defense techniques. For advanced martial artists, however, this art also contains numerous techniques in which objects can be used to defeat a potential opponent. These tools, in this book referred to as “weapons", can be traditional Asian weapons as well as contemporary common objects. In this book (DIN A4 Size), exemplary techniques of this group are described by text and with more than 2500 colour photographs, and a variety of training possibilities are offered to the advanced martial artist. All techniques are shown learnable step by step.

Product details

- Publisher : epubli; 1st edition (11 May 2020)

- Language : German

- Hardcover : 408 pages

- ISBN-10 : 3752950617 ISBN-13 : 978-3752950618

About the author and other contributors

Detlef Klos was already interested in Asia, Asian history, and Asian culture as a teenager. He came to judo in 1966 and started the Korean martial art Hapkido a year later. He has been doing this for over 50 years and was honored with the 9th Dan and the title Grandmaster by the Korean World Association for his skills and his commitment to Hapkido.

Hapkido, die Kunst der Selbstverteidigung, wird in Deutschland seit Mitte der sechziger Jahre ausgeübt. Von koreanischen Großmeistern in ihrer Heimat entwickelt und perfektioniert, waren es in Zeiten des Wirtschaftswunders koreanische Gastarbeiter, welche diese Kampfkunst nach Deutschland brachten. Im Zuge der "Eastern-Welle" in den achtziger Jahren kamen dann weitere koreanische Meister, die gewerbliche Schulen eröffneten und dort lehren. Hapkido, Koreanische Kunst der Selbstverteidigung ist ein umfassendes und reich bebildertes Handbuch dieser modernen koreanischen Kampfkunst und gibt einen umfassenden Überblick über Geschichte, Hintergründe und Techniken.

Das Buch umfasst das ganze Hapkido System von Abwehrtechniken gegen unbewaffnete Angreifer, Abwehrtechniken gegen bewaffnete Angriffe, sowie den Gebrauch traditioneller, aber trotzdem aktueller Waffen zur Selbstverteidigung, und bietet dem Anfänger, Fortgeschrittenen und Meister eine Vielzahl von Trainingsmöglichkeiten neuer, effektiver Selbstverteidigungstechniken, die Schritt für Schritt leicht erlernbar dargestellt werden.

- Herausgeber:

- Westarp Book On Demand; 1., Edition (20. April 2009)

- Sprache: Deutsch

- Gebundene Ausgabe: 377 Seiten

- ISBN-10: 3868053360

- ISBN-13: 978-3868053364

Hapkido, the art of self-defence, has been practised in Germany since the mid-1960s. Developed and perfected by Korean Grandmasters in their homeland, it was Korean guest workers who brought this martial art to Germany during the economic boom. In the wake of the "Eastern Wave" in the 1980s, more Korean masters came and opened trade schools and taught there. Hapkido, the Korean art of self-defence is a comprehensive and richly illustrated manual of this modern Korean martial art and provides a comprehensive overview of its history, background, and techniques.

The book covers the entire Hapkido system of defence techniques against unarmed attackers, defence techniques against armed attacks, as well as the use of traditional, but still up-to-date weapons for self-defence, and offers the beginner, advanced and master a variety of training opportunities for new, effective self-defence techniques, the step be presented in a way that is easy to learn step by step.

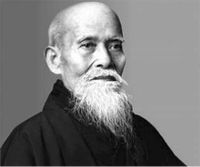

Takeda Sōkaku (jap. 武田 惣角; * 4. November 1859 (traditionell: Ansei 6/10/10) in Lehen Aizu; † 25. April 1943)

war ein Samurai aus dem Takeda-Klan und ein bekannter Kampfkunstlehrer. Er wurde als Neuentdecker des Daitō-ryū und als Lehrer von Morihei Ueshiba, dem Begründer des Aikidō, sowie von Choi Yong-sul und Dr. Jang In Mok, die Begründer des Hapkido, bekannt.

Als Junge erlernte Takeda Sōkaku von seinem Vater Kenjutsu, Bōjutsu und Sumō. Im Jahr 1875 besuchte er Saigō Tanomo in seinem Kloster, um Priesterunterricht zu erhalten. Dort erlernte er auch Oshikiuchi.

born in South Korea on the 15th August 1915, Jang In Mok went to Japan in 1928 and began studying Daito-Ryu Aikijujitsu and finished all requirements on the 30th August 1938 and was awarded a Certificate from Matsuda Yutaka a student of Takeda Sokaku.

Matsuda Yutaka was first a student Doshin So, the founder of Shorinji Kempo in Japan.

Jang said his teacher told him of another Korean studying with Takeda but they never met until afterwards.

Years later in 1956 in Daegu City, South Korea and Jang heard the sounds of martial arts training and went over and met Choi Young Sul. They figured out they had both trained in the same art in Japan.

Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平 Ueshiba Morihei, December 14, 1883 – April 26, 1969) was a martial artist and founder of the Japanese martial art of Aikido.

He is often referred to as "the founder" Kaiso (開祖) or Ōsensei (大先生/翁先生), "Great Teacher".

Von Aikidōka wird er häufig Ō Sensei (翁先生) genannt, was so viel wie Altmeister bzw. altehrwürdiger Lehrer bedeutet. Dieser Titel wurde allerdings vor allem im gesprochenen Japanisch verwendet. Dadurch kam es zu einer anderen Interpretation von Ō sensei als 大先生, also großer Meister, die heute im Westen vorherrschend ist und teilweise auch in Japan Verwendung findet.

Kindheit und Jugend

Er war das vierte Kind und ältester Sohn einer wohlhabenden Familie. Der Vater Ueshiba Yoroku war ein angesehener Bauer und seine Mutter Itokawa Yuki stammte aus einer adligen, landbesitzenden Familie.

Mit ungefähr sieben Jahren studierte Ueshiba auf Geheiß seines Vaters konfuzianische Klassiker und buddhistische Schriften. Sein Vater unterwies ihn in Sumō und Schwimmen.

Ueshiba absolvierte die höhere Grundschule in Tanabe und ging anschließend im Alter von siebzehn Jahren auf die Mittelschule, die er allerdings nicht lange besuchte und sich stattdessen entschloss, sein Studium auf der Handelsschule von Yoshida neu aufzunehmen.

Tätigkeit als Händler und Beginn des Kampfstudiums

1902 schied er aus der lokalen Steuerbehörde aus, bei der er seinen Dienst während seines Schulbesuchs aufnahm, und ging nach Tōkyō, wo er als Händler ein Geschäft für Schreibwaren und Schulbedarf im Handelsviertel von Nihombashi betrieb.

Zur selben Zeit begann er mit dem Kampfstudium des traditionellem Jūjutsu und Kenjutsu; wegen einer Beriberi-Erkrankung musste er dies jedoch abbrechen und nach Tanabe zurückkehren. Dort heiratete er sehr bald Itokawa Hatsu (* 1881). 1903 trat Ueshiba Morihei als Freiwilliger der Armee in Ōsaka bei und nahm wenige Jahre später am russisch-japanischen Krieg teil.

Nachdem er wegen seiner Tapferkeit und seines Muts auf dem Schlachtfeld zum Feldwebel befördert wurde, schickte man Ueshiba auf Heimaturlaub. Diesen nutzte er, um im Nakai Masakatsu Dōjō den Gotō-Stil des Yagyū-ryū Jūjutsu zu erlernen.

1907 entließ ihn die Armee. Er kehrte nach Tanabe zurück, wo er auf dem Hof der Familie Ueshiba arbeitete. Zeitgleich engagierte Ueshiba Yoroku den Jūdōka Takagi Kiyo'ichi, um Morihei in der eigens zum Dōjō umgebauten Scheune unterrichten zu lassen.

1912 nahm Ueshiba Morihei an einem Programm der Regierung teil und siedelte mit weiteren Mitstreitern auf den nördlichen Teil der Insel Hokkaidō um. Ueshiba setzte sich neben seiner Betätigung als Landwirt in den kommenden Jahren für die sozialen Lebensumstände wie verbesserte Wohnbedingungen und die Bildung einer Grundschule in der Siedlung ein. Während dieser Zeit lernte er den Daitō-Ryū-Meister Sokaku Takeda kennen, bei dem er nach intensivem Training sein Daitō-ryū-Jūjutsu-Diplom erlangte.

Ueshiba-Akademie

Ueshiba Morihei pflegte Freundschaft zu Deguchi Onisaburō, dem Mitbegründer der religiösen Ōmoto-kyō-Sekte. Besonders nach dem Tod seines Vaters am 2. Januar 1920 ließ er sich von Deguchi auf der Suche nach spirituellem Leben leiten. Ueshiba zog zu Deguchi nach Ayabe, wo Deguchi ihn beim Bau eines Dōjōs unterstützte, das als Ursprung für die Ueshiba-Akademie dienen sollte. Zuerst unterrichtete Ueshiba nur die Anhänger der Ōmoto-kyō-Sekte. Nach einiger Zeit sprach sich herum, dass ein außerordentlicher Budō-Meister in Ayabe unterrichte. Somit schrieben sich immer mehr Leute, die nicht der Sekte angehörten, in der Akademie ein.

Ungefähr 1921 nach dem ersten Ōmoto-Vorfall, bei dem Deguchi und weitere Sekten-Anhänger festgenommen wurden, begann Ueshiba seine Übungen mehr spirituell zu gestalten. Er wich immer mehr vom klassischen Stil des Yagyu-ryū und Daitō-ryū ab und entwickelte auf der Basis bewährter Prinzipien seinen eigenen Stil. Offiziell nannte er diesen Stil Aiki-Bujutsu. In der Bevölkerung war er aber als Ueshiba-ryū Aiki-Bujutsu bekannt.

Verfeinerung der Kampfkunst

Von dem Zeitpunkt an verfeinerte Ueshiba Morihei seine Kampfkunst bis zu seinem Tode. Die spirituelle Entwicklung trat dabei immer mehr in den Vordergrund und wirkte sich auch auf die Techniken aus, was nicht zuletzt auf diverse einschneidende Erlebnisse zurückzuführen ist. Im Frühling 1925 habe Ueshiba nach einem Kampf, während dessen er die Bewegungen des Gegners vorhersehen konnte, eine Erleuchtung erfahren, über die sein Sohn Kisshomaru berichtet: „Plötzlich hatte er das Gefühl, in goldenem Licht zu baden, das sich vom Himmel über ihn ergoss“ und ihm wurde „die Einheit des Universums mit dem eigenen Selbst klar, und er verstand der Reihe nach die anderen Prinzipien, auf denen das Aikidō basiert.“

Er änderte den Namen von Aiki-Bujutsu in Aiki-Budō, da das Dō auf in der Kampfkunst enthaltene philosophische Prinzipien hinweist. Ende der 1920er-Jahre hielt Ueshiba Kampfkunstkurse in Tokyo ab, wo er in den 1930er-Jahren das Kobukan-Dōjō unterhielt.[2] Mit der Beteiligung Japans am Zweiten Weltkrieg zog sich Ueshiba nach Iwama zurück, wo er sich wieder dem Landbau zuwandte und ein weiteres Dōjō eröffnete. Um 1941 fand der Name Aikidō erstmals Erwähnung.

Harmonie und Liebe als Mittel

Nach seinem letzten Kriegseinsatz in der Mandschurei entwickelte sich Ueshiba Morihei zu einem sehr friedfertigen Menschen. Eine Haltung, die auch in die Philosophie des Aikidō einfloss. 1961 besuchte Ueshiba Morihei auf Einladung Hawaii und sagte, dass er nach Hawaii gekommen sei, um eine „silberne Brücke” zu bauen. Er sehe die im Aikidō enthaltene Harmonie und Liebe als ein Mittel, die Menschen der Welt zu vereinen.

Literatur

Morihei Ueshiba (植芝 盛平 Ueshiba Morihei, December 14, 1883 – April 26, 1969) was a martial artist and founder of the Japanese martial art of Aikido.

He is often referred to as "the founder" Kaiso (開祖) or Ōsensei (大先生/翁先生), "Great Teacher".

The son of a landowner from Tanabe, Ueshiba studied a number of martial arts in his youth, and served in the Japanese Army during the Russo-Japanese War. After being discharged in 1907, he moved to Hokkaidō as the head of a pioneer settlement; here he met and studied with Takeda Sokaku, the founder of Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu. On leaving Hokkaido in 1919, Ueshiba joined the Ōmoto-kyō movement, a Shinto sect, in Ayabe, where he served as a martial arts instructor and opened his first dojo.

He accompanied the head of the Ōmoto-kyō group, Onisaburo Deguchi, on an expedition to Mongolia in 1924, where they were captured by Chinese troops and returned to Japan. The following year, he experienced a great spiritual enlightenment, stating that, "a golden spirit sprang up from the ground, veiled my body, and changed my body into a golden one." After this experience, his martial arts skill appeared greatly increased.

Ueshiba moved to Tokyo in 1926, where he set up the Aikikai Honbu Dojo. In the aftermath of World War II the dojo was closed, but Ueshiba continued training at another dojo he had set up in Iwama. From the end of the war until the 1960s, he worked to promote aikido throughout Japan and abroad. He died from liver cancer in 1969.

Morihei Ueshiba was born in Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan on December 14, 1883, the fourth child (and only son) born to Yoroku Ueshiba and his wife Yuki.

The young Ueshiba was raised in a somewhat privileged setting. His father was a rich landowner who also traded in lumber and fishing and was politically active. Ueshiba was a rather weak, sickly child and bookish in his inclinations. At a young age his father encouraged him to take up sumo wrestling and swimming and entertained him with stories of his great-grandfather Kichiemon, who was considered a very strong samurai in his era. The need for such strength was further emphasized when the young Ueshiba witnessed his father being attacked by followers of a competing politician.

At the age of six Ueshiba was sent to study at the Jizōderu Temple, but had little interest in the rote learning of Confucian education. However, his schoolmaster was also a priest of Shingon Buddhism, and taught the young Ueshiba some of the esoteric chants and ritual observances of the sect, which the Ueshiba found intriguing. He went to Tanage Higher Elementary School and then to Tanabe Prefectural Middle School, but left formal education in his early teens, enrolling instead at the a private abacus academy, the Yoshida Institute, to study accountancy.

On graduating from the academy, he worked at a local tax office for a few months, but the job did not suit him and in 1901 he left for Tokyo, funded by his father. Ueshiba Trading, the stationery business which he opened there was short-lived; unhappy with life in the capital, he returned to Tanabe less than a year later after suffering a bout of beri-beri. Shortly thereafter he married his childhood acquaintance Hatsu Itokawa.

In 1903, Ueshiba was called up for military service. He failed the initial physical examination, being shorter than the regulation 5 feet 2 inches (1.57 m). To overcome this, he stretched his spine by attaching heavy weights to his legs and suspending himself from tree branches; when he re-took the physical exam he had increased his height by the necessary half-inch to pass.[5] He was assigned to the Osaka Fourth Division, 37th Regiment, and was a corporal by the following year; after serving on the front lines during the Russo-Japanese War he was promoted to sergeant. He was discharged in 1907, and again returned to his father's farm in Tanabe. Here he befriended the writer and philosopher Minakata Kumagusu, becoming involved with Minakata's opposition to the Meiji government's Shrine Consolidation Policy.

He and his wife had their first child, a daughter named Matsuko, in 1911.

Ueshiba studied several martial arts during his early life, and was renowned for his physical strength during his youth.[8] His training in Gotō-ha Yagyū-ryu under Masakatsu Nakai was sporadic due to his military service, although he was granted a diploma in the art within a few years. In 1901 he received some instruction from Tozawa Tokusaburōin in Tenjin Shin'yō-ryū jujutsu and he studied judo with Kiyoichi Takagi in Tanabe in 1911.[2][6]

Hokkaidō

In 1912, Ueshiba and his wife left Tanabe and moved to Japan's northernmost island, Hokkaidō.[6] At the time, Hokkaidō was still largely unsettled by the Japanese, being occupied primarily by the indigenous Ainu. Ueshiba was the leader of the Kishū Settlement Group, a collective of eighty-five pioneers who intended to settle in the Shirataki district and live as farmers.

Poor soil conditions and bad weather led to crop failures during the first three years of the project, but the group still managed to cultivate mint and farm livestock. The burgeoning timber industry provided a boost to the settlement's economy, but a fire in 1917 razed the entire village, leading to the departure of around twenty families. Ueshiba, elected to the village council that year, led the reconstruction efforts. In the summer of 1918, Hatsu gave birth to their first son, Takemori.

In Hokkaidō, the young Ueshiba met Takeda Sokaku, the founder of Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu at the Hisada Inn in Engaru, in March 1915. Ueshiba was deeply impressed with Takeda's martial art. He requested formal instruction and began studying Takeda's style of jūjutsu in earnest, going so far as to construct a dojo at his home and inviting his new teacher to be a permanent house guest. He received a kyoju dairi certificate, or teaching license, for the system from Takeda in 1922, when Takeda visited him in Ayabe.[9]:36 He also received a Yagyū Shinkage-ryū sword transmission scroll from Takeda. Ueshiba then became a representative of Daitō-ryū, toured with Takeda as a teaching assistant and taught the system to others.

Onisaburo Deguchi and Ōmoto-kyō

In November 1919, Ueshiba learned that his father Yoroku was ill, and was not expected to survive. Leaving most of his possessions to Sokaku, Ueshiba left Shirataki with the apparent intention returning to Tanabe to visit his ailing parent. En route, however, he made a detour to Ayabe, near Kyoto, intending to visit Onisaburo Deguchi, the spiritual leader of the Ōmoto-kyō religion in Ayabe. Having met Deguchi, Ueshiba stayed at the Ōmoto-kyō headquarters for several days.

On his return to Tanabe, he found that his father had died. Within a few months, he was back in Ayabe, having decided to become a full-time student of Ōmoto-kyō. In 1920 Deguchi asked Ueshiba to become the group's martial arts instructor, and a dojo—the first of several that Ueshiba was to lead—was constructed on the centre's grounds.

Ueshiba also taught Takeda's Daitō-ryū in neighbouring Hyōgo Prefecture during this period.[12] His second son, Kuniharu, was born in 1920 in Ayabe, but died from illness the same year, along with three-year-old Takemori.

Ueshiba in his Ayabe dojo, circa 1922

In 1921, in an event known as the First Ōmoto-kyō Incident (Ōmoto jiken), the Japanese authorities raided the compound, destroying the main buildings on the site and arresting Deguchi on charges of lèse-majesté.[13] Ueshiba's dojo was undamaged, however, and over the following two years he worked closely with Deguchi to reconstruct the group's centre, becoming heavily involved in farming work. His son Kisshomaru Ueshiba was born in the summer of 1921.[6]

Three years later, in 1924, Onisaburo Deguchi led a small group of Ōmoto-kyō disciples, including Ueshiba, on a journey to Mongolia at the invitation of retired naval captain Yutaro Yano and his associates within the ultra-nationalist Black Dragon Society. Deguchi's intent was to establish a new religious kingdom in Mongolia, and to this end he had distributed propaganda suggesting that he was the reincarnation of Genghis Khan.[14] Allied with the Mongolian bandit Lu Zhankui, Deguchi's group were arrested in Tongliao by the Chinese authorities—fortunately for Ueshiba, whilst Lu and his men were executed by firing squad, the Japanese group were released into the custody of the Japanese consul. They were returned under guard to Japan, where Deguchi was imprisoned for breaking the terms of his bail.

After returning to Ayabe, Ueshiba began a regimen of spiritual training, regularly retreating by himself to the mountains or performing misogi in the Nachi Falls. As his prowess as a martial artist increased, his fame began to spread. He was challenged by many established martial artists, some of whom subsequently became his students after being defeated by him. In the autumn of 1925 he was asked to give a demonstration of his art in Tokyo, at the behest of Admiral Isamu Takeshita; one of the spectators was Yamamoto Gonnohyōe, who requested that Ueshiba stay in the capital to instruct the Imperial Guard in his martial art. After a couple of weeks, however, Ueshiba took issue with several government officials who voiced concerns about his connections to Deguchi; he cancelled the training and returned to Ayabe.

Ōmoto-kyō priests still oversee the Aiki-jinja Taisai ceremony in Ueshiba's honor every April 29 at the Aiki Shrine in Iwama.

Tokyo

Ueshiba in Tokyo in 1939

In 1926 Takeshita invited Ueshiba to visit Tokyo again. Ueshiba relented and returned to the capital, but while residing there was stricken with a serious illness. Deguchi visited his ailing student and, concerned for his health, commanded Ueshiba to return to Ayabe. The appeal of returning increased after Ueshiba was questioned by the police following his meeting with Deguchi; the authorities were keeping the Ōmoto-kyō leader under close surveillance.

Angered at the treatment he had received, Ueshiba went back to Ayabe again. Six months later, however, and this time with Deguchi's blessing, he and his family moved permanently to Tokyo. Arriving in October 1927, they set up home in the Shirokane district. The building, however, was too small to house the growing number of aikido students, and so the Ueshibas moved to larger premises, first in Mita district, then in Takanawa, and finally to a purpose-built hall in Shinjuku. This last location, originally named the Kobukan 皇武館, would eventually become the Aikikai Hombu Dojo. During its construction, Ueshiba rented a property nearby, where he was visited by Jigoro Kano, the founder of judo.[

In 1932, Ueshiba's daughter Matsuko was married to the swordsman Kiyoshi Nakakura, who was adopted as Ueshiba's heir under the name Morihiro Ueshiba. The marriage ended after a few years, and Nakakura left the family in 1937.

Between 1940 and 1942 he made several visits to Manchukuo (Japanese occupied Manchuria) where he was the principal martial arts instructor at Kenkoku University.[9]:63

Iwama

From 1935 onwards, Ueshiba had been purchasing land in Iwama in Ibaraki Prefecture. In 1942, having acquired around 17 acres (6.9 ha; 0.027 sq mi) of farmland there, he left Tokyo and moved to Iwama permanently, settling in a small farmer's cottage. Here he founded the Aiki Shuren Dojo, also known as the Iwama dojo.[6] During all this time he traveled extensively in Japan, particularly in the Kansai region teaching his aikido. Despite the prohibition on the teaching of martial arts after World War II, Ueshiba and his students continued to practice in secret at the Iwama dojo; the Hombu dojo in Tokyo was in any case being used as a refugee centre for citizens displaced by the severe firebombing.

The prohibition (on aikido, at least) was lifted in 1948 with the creation of the Aiki Foundation, established by the Japanese Ministry of Education with permission from the Occupation forces. The Hombu dojo re-opened the following year. After the war, however, Ueshiba delegated most of the work of running the Hombu dojo and the Aiki Federation to his son Kisshomaru, choosing to spend much of his time in prayer, meditation, calligraphy and farming.[9]:66–69 He still travelled extensively to promote aikido, however, even visiting Hawaii in 1961.[5]:xix He also appeared in a television documentary on aikido: NTV's The Master of Aikido, broadcast in January 1960.[6]

In his later years, he was regarded as very kind and gentle as a rule, but there are also stories of terrifying scoldings delivered to his students. For instance, he once thoroughly chastised students for practicing jō (staff) strikes on trees without first covering them in protective padding.[

Death

In 1969, Ueshiba became ill. He led his last training session on March 10, and was subsequently taken to hospital where he was diagnosed with cancer of the liver. He died suddenly on April 26, 1969. Two months later, his wife Hatsu also died.(植芝 はつ; Ueshiba Hatsu, née Itokawa Hatsu;

Development of Aikido

Aikido—usually translated as the Way of Unifying Spirit or the Way of Spiritual Harmony—is a fighting system that focuses on throws, pins and joint locks together with some striking techniques. It is unusual among the martial arts for its heavy emphasis on protecting the opponent and on spiritual and social development.[20]

Ueshiba developed aikido after experiencing three instances of spiritual awakening. The first happened in 1925, after Ueshiba had defeated a naval officer's bokken (wooden katana) attacks unarmed and without hurting the officer. Ueshiba then walked to his garden and had a spiritual awakening.

I felt the universe suddenly quake, and that a golden spirit sprang up from the ground, veiled my body, and changed my body into a golden one. At the same time my body became light. I was able to understand the whispering of the birds, and was clearly aware of the mind of God, the creator of the universe.

At that moment I was enlightened: the source of budō [the martial way] is God's love – the spirit of loving protection for all beings ...

Budō is not the felling of an opponent by force; nor is it a tool to lead the world to destruction with arms. True Budō is to accept the spirit of the universe, keep the peace of the world, correctly produce, protect and cultivate all beings in nature.

His second experience occurred in 1940 when engaged in the ritual purification process of misogi.

Around 2am as I was performing misogi, I suddenly forgot all the martial techniques I had ever learned. The techniques of my teachers appeared completely new. Now they were vehicles for the cultivation of life, knowledge, and virtue, not devices to throw people with.

His third experience was in 1942 during the worst fighting of World War II, Ueshiba had a vision of the "Great Spirit of Peace"

The Way of the Warrior has been misunderstood. It is not a means to kill and destroy others. Those who seek to compete and better one another are making a terrible mistake. To smash, injure, or destroy is the worst thing a human being can do. The real Way of a Warrior is to prevent such slaughter – it is the Art of Peace, the power of love.

Retouched photograph of Takeda Sokaku.

The technical curriculum of aikido was undoubtedly most greatly influenced by the teachings of Takeda Sokaku. The basic techniques of aikido seem to have their basis in teachings from various points in the Daitō-ryū curriculum.[24] In the earlier years of his teaching, from the 1920s to the mid-1930s, Ueshiba taught the Daitō-ryū aiki-jūjutsu system; his early students' documents bear the term aiki-jūjutsu.[25] Indeed, Ueshiba trained one of the future highest grade earners in Daitō-ryū, Takuma Hisa, in the art before Takeda took charge of Hisa's training.

The early form of training under Ueshiba was noticeably different from later forms of aikido. It had a larger curriculum, increased use of strikes to vital points (atemi) and a greater use of weapons. The schools of aikido developed by Ueshiba's students from the pre-war period tend to reflect the harder style of the early training. These students included Kenji Tomiki (who founded the Shodokan Aikido sometimes called Tomiki-ryū), Noriaki Inoue (who founded Shin'ei Taidō), Minoru Mochizuki (who founded Yoseikan Budo), Gozo Shioda (who founded Yoshinkan Aikido). Many of these styles are therefore considered "pre-war styles", although some of these teachers continued to train with Ueshiba in the years after World War II.

Later, as Ueshiba seemed to slowly grow away from Takeda, he began to change his art. These changes are reflected in the differing names with which he referred to his system, first as aiki-jūjutsu,[25] then Ueshiba-ryū, Asahi-ryū,[28] and aiki budō. In 1942, the martial art that Ueshiba developed finally came to be known as Aikido.

As Ueshiba grew older, more skilled, and more spiritual in his outlook, his art also changed and became softer and more circular. Striking techniques became less important and the formal curriculum became simpler. In his own expression of the art there was a greater emphasis on what is referred to as kokyū-nage, or "breath throws" which are soft and blending, utilizing the opponent's movement in order to throw them. Ueshiba regularly practiced cold water misogi, as well as other spiritual and religious rites, and viewed his studies of aikido as part of this spiritual training.

Morihei Ueshiba: Budo. das Lehrbuch des Gründers des Aikidō. Kristkeitz, Heidelberg 1997, ISBN 3-921508-57-6.

John Stevens: Unendlicher Friede. Die Biographie des Aikido-Gründers Morihei Ueshiba. Kristkeitz, Heidelberg 1995, ISBN 3-921508-89-4